Ethnographies: Self Reflection in Life Writing

by Enito Mock

Hi All. Unfortunately we didn’t get a chance to read any ethnographies in the course and its a qualitative technique that I love. As a Sociology and Psychology major at the City College of New York, I read quite a bit of ethnographies in my day. Some of the ones I loved was Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life in the City by Elijah Anderson, Rachel and her Children by Jonathan Kozol, Sidewalk by Mitchell Duneier, and Unequal Childhoods by Annette Lareau. There was something about ethnographies that dragged me in. Being able to follow others in their footsteps and see how they lived, felt, and survived a situation is ideally in my mind something I am very interested in. In thinking about ethnographies as life writing, I had asked Dr. Hintz if this would be okay as a research paper

“As I was reading Kozol’s Rachel and Her Children this past weekend, I came to realize that an ethnography not only gives readers insight into the lives of others but also challenges our own perceptions and stereotypes of these populations we read about. Often when we read ethnographies, we go into the descriptive writing with an intent to read more about the lives of others ie. the homeless, African Americans, Chicana and Chicanos, etc. But when we begin to read them and begin to understand more about the lives of others, we have an opportunity to realize (lightbulb moment) that what we think about people are wrong.

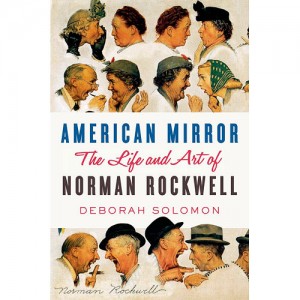

In thinking about this, I would like to explore ethnographies as a life writing and show how ethnographies are not only good to talk about the lives of others in a descriptive way, but also how we can reflect upon them as well to shed a light on what we think is true/untrue. I would also like to talk about the advantages of ethnographies as a reflective glass, in which we can relate to the subjects more so than individual subjects. This is not to say that we can’t relate to Malcolm X or Florence Nightingale, but I think we can relate more to what is going on in our communities which makes us informed citizens in society. ”

I look forward to writing this paper and understanding more about ethnographies as a reflective mirror.

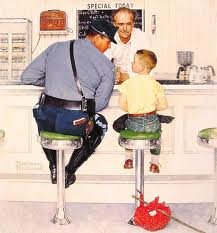

ic tendencies in his paintings. His 1968 painting The Runaway is an example of his love for men.

ic tendencies in his paintings. His 1968 painting The Runaway is an example of his love for men. An earlier example of a society served by the suffering of a child is Ursula Le Guin’s 1973 short story,

An earlier example of a society served by the suffering of a child is Ursula Le Guin’s 1973 short story,

![[UNSET]](https://lifewriting.commons.gc.cuny.edu/files/2013/11/UNSET-300x225.jpg)