Who was Theresa Hak Kyung Cha?

by Enito Mock

Hi everyone! Before I post my discussion questions for this week’s class, I wanted to post a brief biography about Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, the author of Dictee. The biography will not only provide background information about Cha but also the influences that impacted her life to write such a meaningful and complex autobiography(ies). I believe that we, as social animals, gain our understanding of the world, our interests, our feelings, our… through our experiences. We would never know anger if no one yelled at us. We would never know what it means to be happy if we didn’t smile. We would never why we cry if we didn’t think about it ourselves. With Dictee, we would have never known why Cha decided to use the language she did, if we didn’t know her life experiences. It is with this in mind as I read Dictee that I came to understand how she came about with such a beautiful text about memory, struggle, and womanhood.

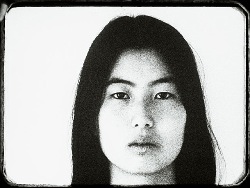

Theresa Hak Kyng Cha

Born: March 4, 1951 in Pusan, Korea.

Passed on: November 5, 1982

Career: Writer, Performance Artist, Filmmaker

Sidelights

In the same year that Theresa Hak Kyung Cha was murdered, she published her one and only book, the partially autobiographical novel Dictee, which she once described, according to Lawrence Chua, in the Village Voice Literary Supplement, as a search for “the roots of language before it is born on the tip of the tongue.”

Language had long interested Cha. Her first concerns appeared when she had to quickly learn the English language after her family immigrated to the United States from Cha’s birthplace in Pusan, Korea, a small town outside of Seoul. She was born during the Korean War and spent the first eleven years of her life moving more than a dozen times, as her parents attempted to find safety. She attended elementary school in Seoul, but her father decided, in 1962, to move to the United States.

The family first moved to Hawaii but shortly afterward settled in San Francisco, where Cha was enrolled in a Catholic school. She and her sister soon discovered that they were the only Asian Americans at the otherwise all-white school and struggled to learn the new language and culture in order to fit in with the rest of the student population.

Later, when Cha advanced to high school, she became fascinated with the French language, which she found to be strangely similar to her native Korean. After studying comparative literature in college, Cha traveled to Paris, where she studied a different kind of language, that of the theory of filmmaking. It was from her studies in France that Cha became involved in putting together a series of essays on film theory in the book Apparatus, Cinematographic Apparatus: Selected Writings (1981), for which she acted as editor.

Cha would go on to create some of her own video-and-film works, all of which focus on the exploration of language, such as her most noted piece, Mouth-to-Mouth (1975), in which a woman attempts to speak, opening and shutting her mouth, struggling to make sounds but unable to produce coherent speech. Abigail Solomon-Godeau, writing for Art in America, summed up the overall themes of Cha’s works with the statement: “Although the wellsprings of Cha’s art are to be found in the experience of immigration and exile, her work can nonetheless be seen to foreground issues related to the difficulty of finding a language, a form of artistic speech, in which to speak ‘otherly.'” This “otherness” can be defined through the eyes and experience of immigrants, in particular, but also through the perspective of all women, in general. Solomon-Godeau continued: “Cha’s art, in its entirety, prompts reflection on the myriad intersections of otherness, exile and femininity.”

Although it was through Cha’s work on film theory as well as her videos and other mixed-media performance pieces that she earned an early reputation, it is for her novel Dictee that she is best remembered. The story contained in this book is of several women. First there is a Korean revolutionary, Yu guan Soon; then Joan of Arc and St. Theresa of Lisieuz make an appearance, as well as Cha’s mother and Cha, herself; also included are the Greek goddesses Demeter and Persephone; and Hyung Soon Huo, a Korean born first-generation immigrant. All of the female characters, as stated by Chua in his Village Voice article, are searching for “the lyric of empowerment.” However, looking at the story from another perspective, a writer for the Web site Voices from the Gap stated that “the element that unites these women’s lives is suffering and the transcendence of suffering.”

Dictee is divided into nine parts, each part dedicated to one of the nine Greek muses, and it focuses on developing metaphors for loss and dislocation. The book has also been described as a collage, as it contains not only various styles of writing, such as poetry, handwritten drafts, historical documents, biographical excerpts, letters, and translation exercises, it also incorporates maps, charts, and photographs. Throughout the work, Cha plays with language, as stated by Juliana Chang in an article in the Encyclopedia of American Literature, through her use of “experimental syntax and sentence construction” in which “sentences and phrases are frequently fragmented, inverted, or repeated.” Chang also stated that Cha’s work is appreciated by a wide variety of critics, which “attests to the richness and profundity of her writing and art. Her work has been described by many as haunting, beautiful, and deeply intelligent.”

Source: “Theresa Hak Kyung Cha.” Contemporary Authors Online. Detroit: Gale, 2004. Literature Resource Center. Web. 5 Nov. 2013.