Heaven’s Coast is the perfect example of the writer’s (Mark Doty) desire of putting in words all his sentiments in a certain period of time. In this case, from the moment Wally, his partner, is diagnosed as an HIV Positive and later as a patient with AIDS, the reading is a mixture of feelings and his book, presented as a memoir, displays not only love, but also compassion, rage, sadness and impotency as the days goes by with a clear, but not imminent outcome: death.

As this subject is very hard to handle, Doty puts reality and romanticism in his words to approach it. He achieves the difficult task to make the reader feel his sorrow and loss, plenty enough to show how it is so difficult to let a loved one go, but to survive with almost any energy and a little will to live without the reason he lived for in the first place. With this in mind, is Doty evidencing his tiredness and almost necessity to this hard situation to end? Did he already make his mind around with the idea of being without Wally after the last months that were hard and unbearable?

The ‘refuges’ as Doty calls the houses/apartments where they lived, are the essence of the couple’s closeness and profound love for each other. Each of them had a different style and was described by Doty with enormous detail to let the reader feel through his words why they were so important in Mark and Wally’s relationship. But as the memoir develops, Doty takes a different approach in every one of them. Does this mean that his memories are changed by grief before and after Wally died? Does the change of scenery was needed to replenish the couple’s faith of avoiding the reality and surpass death?

As Doty presents the importance of taking advantage of every day since Wally was diagnosed, he asks what they would do with this time life has given to them. The memories he described, felt, as they were not only precious but also as normal as possible. In the memoir, Doty insists that he made Wally’s almost unaware of his concern of losing him which leads to an extreme isolation when he was out for work. Does the memoir represent the feelings of Marc Doty when he was away, two days a week, when Wally was decaying? Does his heart and mind needed to be strengthen (with his alone time) to be there for Wally physically and emotionally when he was back?

The importance of the moment of detachment, when Wally dies and he is cremated with only the quilt Mark Doty had sewed is a message of how the two of them were bonded forever. He describes how difficult was for him to let his partner go but it is how he describes the arrival of his ashes, in a cold box, when the reader realizes how difficult and somber this moment was for him. Doty tries to explain his desolation to the reader using common language and even asking questions, as he was looking for an answer from the reader. This memoir was written a few weeks after Wally’s death, which means that Doty’s feelings were still fresh and grieve was becoming relief. It’s Doty trying to release his inner sentiments by writing this memoir? Was it to soon? Or it was imperative to present to the world the difficult time an AIDS patient (partners, family and friends) goes through to achieve awareness and consciousness by society?

Mark Doty expressed: “Not that things need to be able to die in order for us to love them, but that things need to die in order for us to know what they are”. These words represent the main goal of Doty’s memoir. Wally’s death was not necessary but it helped Doty to really appreciate the relationship he had with him and over all, he met a different Wally in each of the stages of his illness and after all the suffering and misery, they loved each other no matter what. Is this work a way to present a common situation, the loss of a loved one, as authentic as possible, with memories that can be shared but not felt?

An earlier example of a society served by the suffering of a child is Ursula Le Guin’s 1973 short story,

An earlier example of a society served by the suffering of a child is Ursula Le Guin’s 1973 short story,

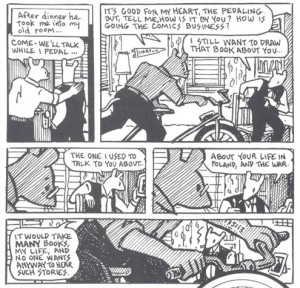

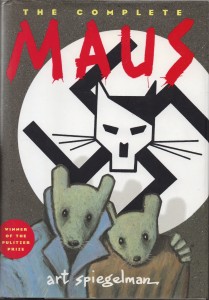

ppeal to my students. It has also fostered their curiosity in learning that a memoir can be read in the form of graphic novel. The lines that separate genre have become blurred to them, and they are left very puzzled and asking very poignant questions (I love it).

ppeal to my students. It has also fostered their curiosity in learning that a memoir can be read in the form of graphic novel. The lines that separate genre have become blurred to them, and they are left very puzzled and asking very poignant questions (I love it).